An Introduction To: Red Burgundy

· Peter Mitchell MW Peter Mitchell MW on

Jeroboams Education is a new series on our blog providing you with the lowdown on the most iconic wine producing regions of the world. Led by our super buying team, Peter Mitchell MW and Maggie MacPherson will introduce you to the key facts and a little history of all the regions you recognise but perhaps don’t know too well. To help really further your education, why not drink along? Browse our Red Burgundy selection.

Introduction

Whilst many very good and some genuinely great Pinot Noirs are made elsewhere in the world, none have yet scaled the heights of the finest Burgundy. At its best it is a wine that has layers of complexity and nuance, a haunting, almost ethereal bouquet, hedonistic dark summer berry fruit flavours, the sweet earthiness of beetroot and textural silky tannins. A wine that is at once rich and light on its feet, powerful and yet elegant and refreshing and a superb accompaniment to food. The production of the heart of Burgundy, the Côte d’Or, is quite small (especially in comparison to Bordeaux for example) and this, combined with the uniqueness of the wines, has meant prices are now out of reach for the majority of consumers. As all vineyards and vintners are not made equal, these excessive prices also make this a region with more ability to underwhelm than almost any other – it is perfectly possible to spend ten times the price of an average bottle in the UK and get something very ordinary in the bottle. Whilst red Burgundy is never cheap, there are more affordable wines – often from the surrounds of the Côte, that offer as good value as Pinot Noir from anywhere in the world.

History

Wine has almost certainly been made here since the 1st century AD or earlier and signs of commercial viticulture remain from the 3rd century and the wines were highly regarded by the 6th century. The first vineyard gifts to monasteries were around this time and by the medieval times, the monks were responsible for producing most of the excellent wine. By the 13th century, the monks of Cluny owned all of the vineyard land around Gevrey, as well as the great vineyards of Vosne (including Romanée Conti, Richebourg and La Tâche), whilst not long afterwards the abbey of Citaux owned the Clos de Vougeot and large tracts of Nuits and the Côte de Beaune. With a highly skilled workforce and the time to learn and study, the monks discovered the importance of terroir and began the process of defining the crus we know today. When the Papal court moved to Avignon in the 14th century, the wines became regarded as the best in the world and demand soared and under the dukes of Burgundy wine was the region’s most important export.

Pinot Noir has probably been here much longer, but is first mentioned in the 1370s, with Gamay also present (and regarded lowly) at the same time. The fall of the dukedom and rise of the power of France saw the vineyards slowly taken from the church and sold to powerful local merchants and the first négocients were founded in the 1720s. The revolution saw the lands confiscated from the church and the nobility and sold in small pieces to multiple owners. The Napoleonic rules of succession meant these were further subdivided with each generation, leading to the fragmented nature of ownership that exists today. The ravages of Phlloxera devastated the region and when the vineyards were replanted, only the best sites saw new vines.

An informal classification already existed, but it was not until the 1930s that the appellation system was introduced. Virtually all Burgundy was matured and sold by the négocient houses until the 1930s when the first co-operatives started to be formed and the likes of Gouges, d’Angerville and especially Rousseau began to bottle their own wine. By the 1960s, 15% of the wine was domaine bottled and that has risen to around half today. The 1980s saw more prosperity come to the region and a new generation took over at often moribund estates. With greater technical expertise and a more outward view, better and better wines were made and prices began their inexorable rise to where they are today. In 1996, a bottle of Echézeaux from Domaine de la Romanée Conti would cost you £50 retail, now a five year old example of the same wine is £2000.

Whilst the region has thus far largely remained in the ownership of the families who have been here for generations (in stark contrast to Bordeaux) the value of the land and French inheritance taxes possess an existential threat to this.

Geography

The basic layout of the Côte d’Or is simple enough, a long limestone outcrop that has weathered over the years, with the limestone being mixed down the gentle slopes in different proportions. High on the slope, the soil is thin, the climate cooler and grapes ripen late. At the bottom of the slope, frost is more of a risk, the soils are deeper, younger and richer and wines from here can be good but are never great. It is towards the centre of the slope, where there is a perfect mix of limestone and marl that the greatest wines are made. The finest vineyards face east or slightly to the south of east, warming them early in the day.

The Côte d’Or is a marginal climate for ripening Pinot Noir and in many years it is a struggle to attain full ripeness before autumn rains arrive in all but the best sites. Chaptalisation (adding sugar to the grape must) is still commonplace, although with better viticulture and rising global temperatures, less so than in the past.

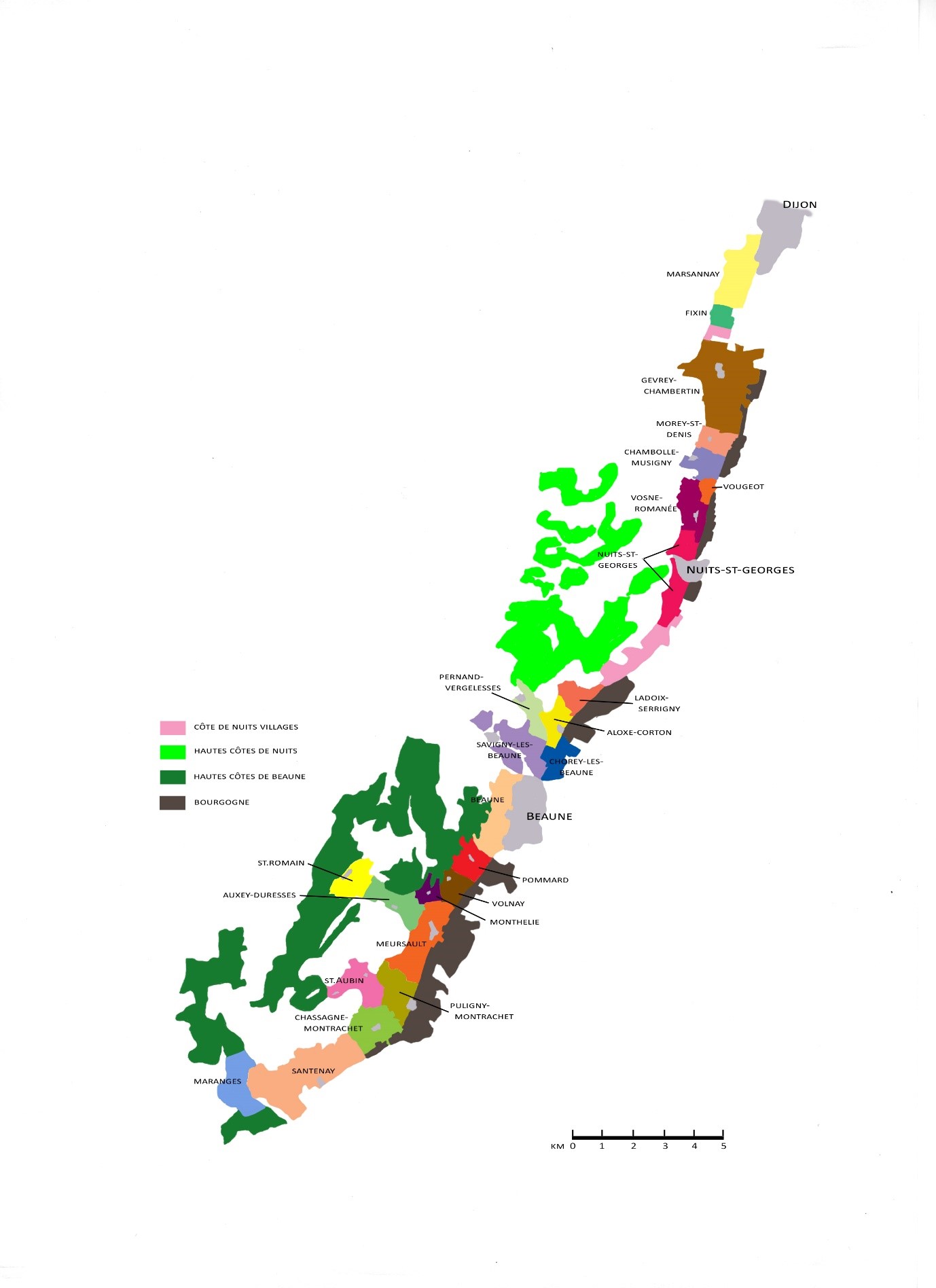

The Côte de Nuits is to the north and runs virtually unbroken from the southern edge of Dijon down to Corgoloin and most of the production is red. The Côte de Beaune runs from Ladoix in the North down to Santenay in the south and is flatter, broader and twice the size of the Côte de Nuits. Around half of the production here is white.

A regular feature of the Côte are the combes that bisect it laterally, acting as a funnel for wind and rain and cooling the vineyards adjacent to them.

To the south, the Côte Chalonnais has similar soils but lacks the escarpment with perfect exposure, so vineyards are more scattered where a south-east exposure is available. Further south still, the Mâconnais is also on limestone, but the terrain is more rolling hills and it is noticeably warmer.

Winemaking

One of the biggest advances in the past 30 years in Burgundy (and indeed in other regions) has been the increase in expenditure on harvesting. Any decent producer now harvests into small containers (to avoid damaging fruit and to get it to the winery more quickly). There, fruit will be sorted to remove under-ripe, rotten or damaged berries. Starting with the best fruit the season can offer is the first step to making good wine. Sadly there are still too many producers who fail at this point.

Burgundy is rare in that some red wine is made with the stems. In most regions, de-stemming is automatic, although there is a rising trend amongst avant-garde winemakers to resurrect the technique worldwide, but here nearly all wine was made with the stems until relatively recently. In anything other than perfect vintages this could give a raw tannic edge to Burgundy. There are still a small band of producers who like to ferment with some or all of the stems. In of themselves, stems give no great flavour to the wine and add tannins which can be quite harsh, so any used must be of very ripe wood. The plus of stems is that the early injection of tannins fixes unstable colour in the must, they can add a measure of complexity and they help drainage of the cap during wine-making, facilitating extraction and temperature control. The intact grapes on whole bunches can also take up to 2 weeks for the berries to rupture, extending fermentation and adding texture through higher levels of Glycerol. They also leach a small amount of alcohol and purple pigments during fermentation. The most famous producer who ferment with whole bunches is Domaine de la Romanée Conti, who routinely keep half the stems and attribute the rose petal aromas in their wines to this, whilst Dujac has also long been a proponent.

Extraction – the key to wine quality -occurs before during and after fermentation and different flavours and tannins are extracted and fixed at each stage. When no alcohol is present, powerful fruity flavours, especially cassis and black cherry are extracted, along with purple colour. Many growers now choose to slow the onset of fermentation for a few days, often by chilling though sometimes with SO2, to carry out this extraction. More than 6-7 days of this makes very dark, monolithic wines that can be impressive but have little sense of terroir.

Fermentation of sugars to alcohol is a very straightforward reaction, but the end result is strongly affected by the size and shape of vessel used, the temperature it happens at and whether the yeast used is cultured or ambient. Higher temperatures tend to extract more colour and flavour, however at 35C and above the danger of yeast death and volatile acidity becomes very real. The cap of skins and juice need to be regularly mixed during fermentation and in Burgundy this is traditionally done by pigeage , or punching down of the cap, rather than by pumping over, which aerates the must and damages its aromatic complexity. Post alcoholic fermentation sees extraction particularly of tannins and so the length of this can dictate the final grip of the wine.

The total time in vat can vary from as little as 12 days up to 4 weeks, but no serious wine will have less than 18 days.

The final stage in wine-making is élevage. The wine is run off from tank to barrel and a certain amount of press wine added. Too little and the wine may lack structure, too much and it will be harsh and dry. Sadly economics can sometime dictate how much is used. In most cases the wine will rest in barrel for between 9 and 24 months, also undergoing malolactic conversion during this period. Great skill and regular tasting are required during this stage as too long in wood will dry a wine out, too much new oak can smother the wines quality, whilst if barrels are not kept regularly topped up, vinegary aromas will start to form. Wines are generally racked twice during élevage to get them off the gross lees and reduce the risk of reduction.

At bottling a grower must decide whether to fine or filter the wine. Either process may remove flavour or texture, but will also add to the long term stability of the wine. Generally the greatest wines are only fined if they are cloudy and are not filtered.

The Classification Structure

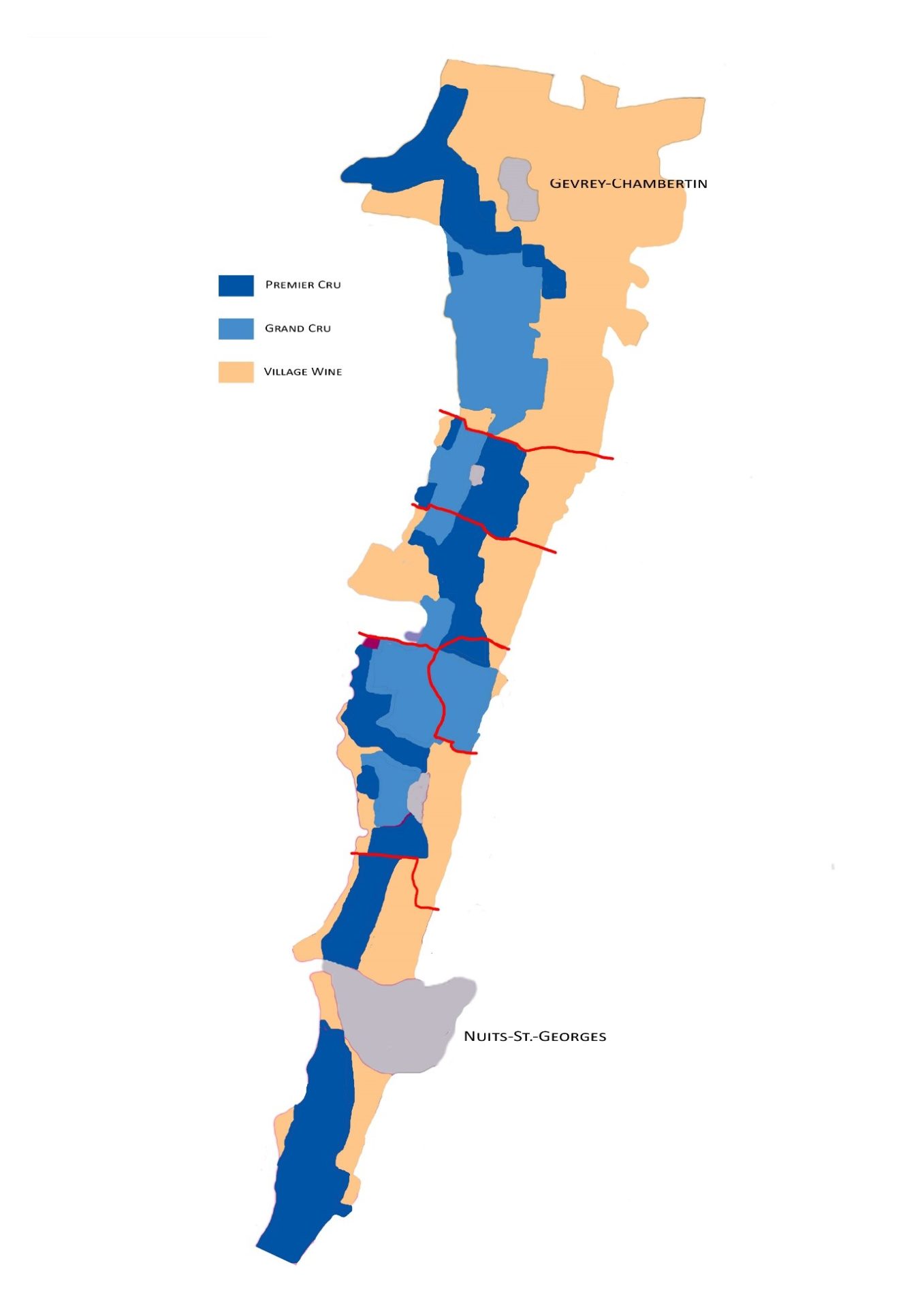

There are four levels of appellation in the Côte d’Or:

Regional: Bourgogne Rouge, Côte de Beaune.

Communale (Village): e.g. Volnay, Nuits-St.-Georges, Beaune.

Premier Cru: Specific vineyards that are deemed to produce wines of a higher quality are classified as premier cru and are named on the label as Village + premier cru, e.g. Vosne-Romanée premier cru. If the wine comes wholly from a single named climat (vineyard), then the name of that climat may also appear on the label, eg Vosne-Romanée premier cru les Suchots.

Grand Cru: 32 individual vineyards spread throughout the Côte (25 for red wine) that are considered exceptional in their own right. The name of the village they are in does not appear on the label In theory, quality rises as you go up the appellation ladder, in practice this is not always the case as some growers are more competent than others. It is also arguable that the original classification of the vineyards is somewhat suspect. It is no coincidence that it was administered from Beaune and 80% of that communes vineyards were rated premier cru. It is also arguable that a large portion of the Clos de Vougeot and most of Echézeaux do not warrant Grand Cru status, whereas several other premier cru vineyards do.

The Red Burgundy Appelations

The Villages of the Côte d’Or from North to South

Marsannay

Key info: Area under vine: 230 Ha; Average production: 110,000 cases; Premier Crus: 0; Grand Crus: 0.

Historically famous for its delicious rosé, Marsannay was elevated to village Appellation Controlée in 1987, which led to a fall in the production of rosé and an increase in red. Rosé still makes up around 15% of production and this i the only village appellation for rosé in the Côte d’Or. Around 15% of production is of leaner fresher styled white that is best drunk young.

Whilst the higher slopes have plenty of clay in them and will never make fine wine, the vineyards between the village and the route national have more gravel over the limestone and increasingly good wine is being made here. The style of the best wines is lighter and very much towards the red fruit end of the spectrum and they can make nice young drinking

Fixin

Key info: Area under vine: 115 Ha; Average production: 55,000 cases; Premier Crus: 6 totalling 18 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Just to the North of Gevrey-Chambertin lies Fixin (pronounced Fissin). The vast majority of production is red (95%) and there are 6 named premier crus, all located in the south near Gevrey, covering 22 Ha. The wines from these soils are very similar to those from northern Gevrey and are powerful and structured. The best premier crus age very well and represent fine value. Village wines can tend to rusticity on occasion, but are generally well priced and have a certain robust pleasure.

Gevrey-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 436 Ha (plus 50 Ha in neighbouring Brochon entitled to use the Gevrey name); Average production: 190,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 26 totalling 86 Ha; Grand Crus: 9 totalling 87 Ha (Chambertin, Chambertin-Clos-de-Bèze, Chapelle-Chambertin, Charmes-Chambertin, Mazis-Chambertin, Griotte-Chambertin, Latricières-Chambertin, Mazoyères-Chambertin, Ruchottes-Chambertin)

Only red wine is made under the Gevrey-Chambertin name and it is one of the most famous names in the world of wine. This is by far the largest commune of the Côte de Nuits and unusually, the village land spreads further to the west than in any other village, a result of the alluvial limestone and gravel (perfect for red wine production) washing further from the slopes than in other villages. The premier crus are in two bands, one to the south of the village and the other, generally superior, to the west, although lying at higher altitude and more exposed to cooling winds from the Hautes-Côtes, in marginal vintages these wines from these premier crus can struggle to live up to their reputation.

The Grand Crus sit in a swathe on east facing land protected by a forest on the hill above and Chambertin and Clos-de Bèze are generally considered the best of these, Latricères and Ruchottes the most tannic and dense.

The wines of Gevrey are characterised by a combination of power and finesse. These are often the most structured and full bodied wines of the region, yet they also have a freshness and elegance. Good Gevrey will take longer to reach maturity than wines from other communes and can have immense longevity.

Morey-St-Denis

Key info: Area under vine: 147 Ha; Average production: 43,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 20 totalling 41 Ha; Grand Crus: 5 totalling 35 Ha (Bonnes-Mares (the majority is in Chambolle), Clos de Tart, Clos des Lambrays, Clos de la Roche, Clos St. Denis)

The second smallest of the Côte de Nuits communes, over half of the land is taken up by premier or grand cru vineyards, yet this is one of the least well known and celebrated villages. The vast majority of production is red, however a very small amount of white villages and premier cru wine is made (currently under 5 Ha is panted to Chardonnay).

The Grand Crus continue their line on the slope from Gevrey, although here a handful of premier crus sit further up the slope beneath the woods above. The majority of the premier crus form a band below the grand crus on the slope, before petering out to village wines at the base.

Morey is one of the hardest communes to pin a style on, as there seems to be great variation between growers, from Dujac’s velvety reds to Groffier’s dense and tannic ones. As befits its position, the styles vary between Gevrey and Chambolle, but average quality tends to be very high.

Of the Grand Crus, Clos de la Roche is probably the star, along with the small portion of Bonnes-Mares that sits in Morey, although in recent years Clos de Tart has seen a resurgence in quality as has Clos des Lambrays which was purchased by LVMH in 2014.

Chambolle-Musigny

Key info: Area under vine: 177 Ha; Average production: 76,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 24 totalling 56 Ha; Grand Crus: 2 totalling 24 Ha (Bonnes-Mares (the majority, a part is in Morey), Musigny)

Chambolle is a very sleepy village which happens to contain two superlative Grand Crus and, in Mugnier, Roumier and de Vogue, three of the region’s greatest producers. The grand crus are at the northern (Bonnes-Mares) and southern (Musigny) extremes of the villages, with a qualitatively mixed bag of premier crus on the slope between them. Of these, Les Amoureuses, which adjoins Musigny, is the top candidate for promotion to Grand Cru and neighbouring Les Charmes can be nearly as good. The other two top premier crus are found next to Bonnes-Mares – Les Fuées and Les Cras.

Chambolle is always red wine, however a small amount of white (about 125 cases) is made in the Musigny Grand Cru by de Vogue (who own around 70% of the entire cru).

Chambolle wine is often said to have more finesse and elegance than any other Pinot noir in the world and it is true that the wines from here can be very seductive in youth and have a vast array of perfumed red and black fruits, but they are not without the structure to age well.

Vougeot

Key info: Area under vine: 64 Ha; Average production: 5,800 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 4 totalling 11 Ha; Grand Crus: 1 totalling 50 Ha (Clos de Vougeot)

The smallest Côte d’Or commune and dominated by its Grand cru, the village and premier cru wines are rarely seen outside of the region. Red and white of both are made (about twice as much of the former). The reds tend to be tannic and solid and not of great merit, whilst the whites can be interesting if a little austere.

The Clos itself is the largest Grand Cru of the Côte de Nuits and is a magnificent walled vineyard of 50 hectares. With 80 owners of vines in the vineyard and a marked difference between the upper and lower parts of the vineyard, there is great variability in style and quality here. Wines from vines at the top of the slope tend to be the best, rather than further down where more clay is in the soil and the water table closer. As a grand cru, Clos de Vougeot disappoints, with more wines than not simply not making the grade. There are some fine growers here and a handful of wines of genuine merit, but probably as much as half of this vineyard should be declassified to premier cru or even village land.

Vosne-Romanée (including Flagey-Echezeaux)

Key info: Area under vine: 220 Ha; Average production: 66,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 14 totalling 57 Ha; Grand Crus: 8 (including 2 in Flagey-Echezeaux) totalling 68 Ha (Echézeaux, Grands-Echézeaux, La Grand Rue, Richebourg, La Romanée, Romanée-Conti, Romanée-St-Vivant, La Tache)

The heart of red burgundy and home to its greatest expressions, Vosne is a fairly small commune that produces only red wines. To the east of the settlement towards the route nationale lies most of the village wine on thin clay limestone soils. On the slope to the west of the village lies a group of grand crus surrounded by premier crus and then in Flagy to the north, the two Echézaux crus. The soils here are still clay limestone, but very thin and topped with limestone scree, allowing perfect drainage. The premier crus are all of high standard, but the best (and frequently better than most Echézeaux) are Les Suchots and Les Beaux Monts.

Of the Grands Crus, Echézeaux is far the biggest at 35 Ha. In the original Grand Cru delimitation of 1936, Echézeaux was a vineyard of just 3.57 Ha and only subsequently were a further 10 climats allowed to use its name. This has made Echézeaux no better than premier cru in quality. Grands Echézeaux , which adjoins the best part of Vougeot, makes indisputably Grand Cru wine of power and finesse and is possibly the best value Grand Cru. Romanée St Vivant lies on the flattest land next to the village and makes a very silky and generous style. Over half is owned by Domaine de la Romanée Conti (DRC) with fine producers owning most of the rest. Richebourg, on higher ground produces richer, meatier wines that demand long cellaring. La Romanée is the smallest Grand Cru and only in the last 20 years has it been worthy of the name. La Grand Rue sits between La Tache and Romanée Conti and until 1992 was classified, somewhat anomalously, as a premier cru. Owned by Domaine Lamarche, its wine is always highly perfumed. The last two Grand Crus are the greatest wines of burgundy and monopolies of the DRC. La Tache is over 3 times the size and fetches slightly less money, yet neither is consistently better than the other, both are near perfection.

Vosne in general is of a remarkably consistent and high quality, with high prices to match, and should have perfume, elegance a lavish richness on the palate, yet also fine and full structure.

Nuits-St.-Georges

Key info: Area under vine: 307 Ha; Average production: 155,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 41 totalling 144 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Nuits extends for some 5km, making it by some way the longest communal appellation (although Gevrey is 40% bigger) and, perhaps, because of this, it also has the greatest variety. It is also the commercial centre of the Côte de Nuits and home to many of the négocients. As elsewhere on the Côte, the lower land near the route nationale is classed as village wine, with the land further up the slope premier cru. There are no Grand Crus in Nuits, although Les Cailles, Les Vaucrains and especially Les Saint Georges can occasionally reach those heights in quality. Around 96% of production is red.

The vineyards can be divided in three, with those to the north of the town on soils similar to Vosne producing a more elegant style, often very similar to Vosne but with an earthy edge. The river Meuzin bisects the appellation through the town and to the south of this are deeper soils with more clay producing the classical Nuits of fuller tannins, robust and a little earthy. 16 of the premier crus are in this section, including the finest ones. Further south lies the village of Prémeaux-Prissey, viticulturally a part of Nuits, where the vineyards reach their narrowest point and where the soils become thin, chalky and stony. The reds from here have greater perfume and elegance, less structure and this is also where some very fine white is made.

As a result of its long history and commercial position, Nuits became the most famous wine of Burgundy after the war with the result that prices were high and quality often execrable. Its reputation as a deep cloured, robust and tannic wine dates from this time, when much of it was illegally cut with cheap Algerian red. The commune is still home to some of the most overpriced and disappointing wine, being traded on the name, however it is also home to some very high quality domaines making excellent wines.

Whilst a single style of the wines here is impossible to pin down, they do tend to a fullness of tannin and a certain muscularity.

Côtes de Nuits Villages

Key info: Area under vine: 168 Ha; Average production: 75,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 0; Grand Crus: 0.

The Côtes de Nuits Villages is a disparate appellation covering vines from 5 villages, that were historically considered superior to regional wines, but not perhaps good enough to have their own appellation. Brochon, and Fixin to the north of Gevrey (although Fixin also has its own appellation) and the parts of Prémaux not included in the Nuits appellation, Comblanchien and Corgoloin to the south of Nuits.

As it is little know or understood, this appellation can offer superb value compared to village wines and some quite serious domaines own land in these villages. For example, Domaine de l’Arlot’s Côtes de Nuits Villages is superior to most merchant’s Nuits St Georges bottlings at a much lower price.

The style of the wines depends on whether they are from the northern 2 villages (similar to Gevrey) or the southern 3 (more like Nuits), but most are made for fairly early drinking.

Ladoix-Serrigny

Key info: Area under vine: 100 Ha; Average production: 44,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 11 totalling 24 Ha; Grand Crus: 2 (shared with Aloxe-Corton) totalling 147 Ha (Corton and Corton-Charlemange).

The wines from here are labelled Ladoix and around two thirds are red. A part of the Grand Crus Corton and Corton-Charlemagne are found in Ladoix and these are some of the earliest ripening sections.

The village reds tend to a soft suppleness, bright red fruits and sometimes a faintly vegetal character. They are often good value and whilst never stellar, can provide fine affordable drinking.

Aloxe-Corton

Key info: Area under vine: 265 Ha; Average production: 50,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 14 totalling 38 Ha; Grand Crus: 2 (shared with Ladoix-Serrigny) totalling 147 Ha (Corton and Corton-Charlemange).

This tiny village below the hill of Corton has the largest Grand Cru of the Côte d’Or and the Côte de Beaune’s sole red Grand cru. 147 hectares of this village is classified as Grand Cru Corton (red), Corton Blanc or Corton Charlemagne (white).

The hill itself has vineyards covering 270 degrees of exposure and multiple soil types, so generalisations are futile. Not only that, but vines in certain plots in neighbouring Ladoix and Pernand can use the Corton appellations. Wines from mid slop and facing south east tend to be much richer and denser than those from the south west exposures. With 200 owners on the hill, the variability in style and quality is immense and it is fair to say that more poor, over-cropped wine is made than great wine. However, in the right hands, Corton can be a majestic wine, rich, powerful and tannic, but with finesse and great longevity.

Wines from the village tend to be overlooked, but can be generous and supple and are frequently good value.

Pernand-Vergelesses

Key info: Area under vine: 178 Ha; Average production: 90,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 8 totalling 83 Ha; Grand Crus: 1 totalling 17.5 Ha (En Charlemagne; labelled Corton when Red, Corton-Charlemagne when White).

This small village, nestled to the north-west of the hill of Corton produced both red and white wine, with a noticeable shift towards white in the last 30 years, with nearly 40% of production now white (although the premier crus are still red dominated). The soils are fine, often with a high limestone content, but many of the vineyards face west and spend much of the day in shade. The vineyards on the valley floor, Ile de Vergelesses and Les Vergelesses get the most sunshine and tend to produce the best wines outside of Corton.

Reds tend to be quite fleshy and robust and have good ageing potential, although care must be taken as there is also much stalky and hard wine made here, especially in years when full ripeness was hard to attain. From a good grower and a good vintage, this appellation can offer fantastic value.

Savigny-Lès-Beaune

Key info: Area under vine: 346 Ha; Average production: 178,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 22 totalling 139 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Just a few kilometres from Beaune in a side valley that also carries the main Paris motorway, Savigny makes both red and white wine, although 85% is red. The soils on the valley floor are quite deep and rich and are all villages land, whilst above this there are two groups of premier crus on thinner, finer soils. The first group, including Serpentiéres has a southerly exposure and ripens a week before the second group, facing north-east and including Marconnets and Narbantons.

Savigny contains some very good growers and in good vintages can offer some fine wines, with ripe fat fruit and a flinty note. In cool vintages the wines can be a bit angular and charmless from all but the best estates.

Chorey-Lès-Beaune

Key info: Area under vine: 133 Ha; Average production: 55,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 0; Grand Crus: 0.

Located on the ‘wrong’ side of the route nationale, Chorey only got its appellation in 1974 and has not a single premier cru. 94% of the production is red and it tends to be ripe, round juicy and fairly light, but also inexpensive.

Beaune

Key info: Area under vine: 412 Ha, plus 35 Ha of Côte de Beaune; Average production: 174,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 42 totalling 318 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

The largest commune of the Côte d’Or and the viticultural capital with many of the leading négocients based in the town. Just over 80% of production is red.

The vineyard, located to the west and north-west of the town, comprises 35 Ha of Côte de Beaune, a lesser appellation on top of the hill, 94 Ha of Beaune AOC and an excessive 318 Ha of premier cru. The best of these, which are certainly worth the title, are found directly north west of the town and are Champs Pimot, Clos des Fèves, Perrières, Bressandes, Grèves, Marconnets and Clos de Mouches.

Much of the vineyard land is owned by the big Beaune négocients and in recent years there has been an overdue increase in the quality of their bottlings. The style of the wines varies considerably, but as a general rule they fall somewhere between the elegance of Volnay and the sturdiness of Pommard, whilst seldom, if ever, reaching the same quality level.

Pommard

Key info: Area under vine: 322 Ha; Average production: 145,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 28 totalling 116 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Historically one of the more famous villages, that had a reputation for making big sturdy wines. Production from the beginning of the 20th century up until the 1960’s was vast compared to now and Pommard was amongst the most widely distributed of names. This meant much of the wine was of dismal quality, made to cash in. As it has gently retreated towards obscurity, the vineyard area has shrunk and the quality has risen. Village Pommard i pleasant, if of no great distinction and tends to be a touch earthy. Only red wine is made in Pommard on soils that have a higher iron and clay content than those of neighbouring villages.

The premier crus are split into two halves by the village, with those toward Beaune making muscular and tannic wine that demands ageing. Epenots is in this section and in the right hands can make wine of Grand Cru quality.. To the south of the village on the road to Volnay, the premier crus are softer, lighter and have more aromatic finesse, the best here is Les Ruigiens.

Volnay

Key info: Area under vine: 220 Ha; Average production: 90,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 29 totalling 133 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

The most delicate and finessed of red burgundies come from this village, similar in style to Chambolle, but somehow more ethereal and fragrant and with a touch less structure. The soils here are limestone with a low portion of clay, resulting in lighter silkier tannins. The premier crus are located in a single band but with distinct varying soil types, but all emphasise silky finesse, with perhaps the finest being the Les Caillerets climat.

One oddity is Volnay-Santenots 1er cru, which is located entirely in Meursault. When white wine is made from one of these 5 climats it is labelled as Meursault, but when it is red it becomes Volnay 1er cru. Santenot’s wine is least typical of the village, having more prominent tannins and a harder edge.

Monthélie

Key info: Area under vine: 123 Ha; Average production: 50,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 15 totalling 37 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

The second smallest commune on the Côte d’Or, for many years most of the production of Monthélie was sold to Beaune négocients and garnered little interest. In recent times, more wine from here has been domaine bottled. The style of the wines is similar to Volnay, in that they can be beautiful perfumed and elegant, but with moderately higher tannin and acid. The best wines come from the premier crus Sur-le Velle and Champs-Fulliot, which are a continuation of Volnay’s Caillerets and Clos des Chênes. Around 90% of the production is red.

Monthélie wine remains largely unknown and can be hugely under-priced for its quality.

Auxey-Duresses

Key info: Area under vine: 133 Ha; Average production: 65,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 9 totalling 29 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Heading up a side valley off the Côte, Auxey has recently started to be more appreciated for both its reds (90% of production) and whites. Attaining full ripeness here can be an issue and in lesser vintages the whites can be tart and reds hard and mean, but in fully ripe vintages, the reds can be characterful, robust and surprisingly powerful, especially those form the premier cru Les Duresses.

Saint-Romain

Key info: Area under vine: 97 Ha; Average production: 43,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 0; Grand Crus: 0.

Not on the Côte d’Or, Saint Romain sits up a side valley beyond Auxey-Duresses and is probably more famous for its cooperage, François Frères, than for its wines. Around 40% of production is red and these are light and refreshing wines that can offer delicious young drinking in better vintages.

Meursault

Key info: Area under vine: 396 Ha; Average production: 210,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 18 totalling 107 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

One of the most famous places in the world for white wine production, Meursault also produces around 4,000 cases of red wine each vintage. Labelling is confusing, with Meursault rouge produced in a handful of climats in the north of the village, the les Caillerets and Les Cras vineyards producing some 1er cru Meursault, then 6 further climats around the hamlet of Blagny in the south of the appellation producing Blagny (and Blagny 1er cru) rouge.

The wines tend to be ripe and fleshy with a relatively loose knit structure and can be good value in riper vintages.

Puligny-Montrachet

Key info: Area under vine: 298 Ha; Average production: 130,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 19 totalling 98 Ha; Grand Crus: 4 totalling 21 Ha (Bâtard-Montrachet (half), Bienvenues-Bâtard-Montrachet, Chevalier-Montrachet, Le Montrachet (majority)).

Legendary white wine village that also makes around 600 cases of red wine each vintage. A rarely seen curiosity, it is light, fruity and lacking any great class.

Chassagne-Montrachet

Key info: Area under vine: 304 Ha; Average production: 180,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 48 totalling 149 Ha; Grand Crus: 3 totalling 10 Ha (Bâtard-Montrachet (half), Criots-Bâtard-Montrachet, Le Montrachet (minority)).

At the end of the second world war, Chassagne was a red wine village, 80% of its production being from Pinot Noir. The 70 years since have seen a marked shift, with only a third of the production now red. Much of the land moved over to white is too fertile to make fine Chardonnay, but as almost all Chassagne appellation vineyards are eligible to be planted with either grape, fashion has driven this unfortunate development.

The area below the village (which is designated AC communale) has deeper soils and is where most of the red is made. Around 16,000 cases of 1er cru red are also made, the finest from a section in the south including the Morgeot climat.

Red Chassagne tends to have quite deep colour, very bright red fruits and fairly firm tannins, not dissimilar to Pommard.

Saint-Aubin

Key info: Area under vine: 157 Ha; Average production: 92,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 20 totalling 117 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Heading up a side valley, St Aubin’s finest vineyards lie adjoining the western edges of Chassagne and Puligny. and then also on a south facing slope beyond the village. A very high proportion of the vineyard area is entitled to 1er cru status and around 25% of production is red. Red St.Aubin tends to be fairly tannic, strong and earthy, with dark fruit profile. They can age very well over 5-10 years, softening and developing a gamey character.

Santenay

Key info: Area under vine: 329 Ha; Average production: 155,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 11 totalling 123 Ha; Grand Crus: 0).

Santenay has long had a reputation for making decent honest and well priced burgundy. Reds make up 85% of production and tend to a rather burly character, when ripe they can be quite powerful with chunky tannins and often a touch of rusticity, when made in a poor cellar they are just weedy and austere. The best are robust in youth but often age surprisingly well. The premier crus of Gravières and Le Comme can produce something with a bit more finesse.

Maranges

Key info: Area under vine: 170 Ha; Average production: 83,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 8 totalling 130 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

The newest village appellation of the Côte d’Or, created I 1988, covers three villages and 90% of the production is red. Previously known as Côte de Beaune, the wines from here are appealingly fruity when young, though seldom improve with cellaring.

The Côte Chalonnais Red Wine Villages

Rully

Key info: Area under vine: 329 Ha; Average production: 175,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 23 totalling 96 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

More famous for its slightly tart appley whites, around a third of the production is honest ordinary red burgundy, which in warmer vintages can have some real character. In cooler years the wines tend to have a green and lean edge to them.

Mercurey

Key info: Area under vine: 646 Ha; Average production: 310,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 32 totalling 161 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

The largest, best known and generally the finest quality village in the Côte Chalonnais, Mercurey produces around four times more red than white wine. The best wines from here are the match of many lesser wines from around Beaune and can represent good value – although prices have been rising steadily since the 1990s. Whilst the number of premier crus has jumped from 5 in the ‘80s to 32 today, they are mostly worth the small premium charged.

Givry

Key info: Area under vine: 269 Ha; Average production: 140,000 cases (village & 1er Cru); Premier Crus: 38 totalling 108 Ha; Grand Crus: 0.

Another village which makes four bottles of red for each bottle of white, the quality tends to be a notch down from Mercurey and wines are fruitier and less structured, however the prices charged tend to be commensurately lower and this is often an introductory point to the wines of the region. Around 40% of the vineyard is now classified as premier cru, somewhat taking away from its meaning.

The Hautes-Côtes

The Hautes-Côtes is divided into two, with either the suffix ‘de Nuits’ or ‘de Beaune’ and encompasses the land in the beautiful rolling hills above the Côte d’Or. At up to 500m altitude, it is noticeably cooler here and in lesser years the wines can be a bit weedy, however with a diligent producer and the effects of global warming, some very good wines can be found here at reasonable prices.

Other red Burgundies

Mâcon Rouge can be made from Gamay and Pinot Noir in any proportions from the large vineyard area to the north-west of Mâcon, although in practice the vast majority is made from Gamay, as Pinot Noir wines can legally be sold as Bourgogne Rouge at a higher price. Around 200,000 cases are made annually.

Bourgogne Rouge is made from Pinot Noir and can come from anywhere in the region, leading to a marked variation in quality and styles. Some fine Bourgogne is made in the Côte d’Or and will have some of the character of the top wines, but the majority is grown in lesser areas such as the Mâconnais and the outlying parts of the Côte Chalonnais. The Hautes-Côtes (the land in the hills above the Côte d’Or) is entitled to use the name, but generally wines from here are sold under the Hautes-Côtes appellation at a higher price. Approximately 2,000 hectares of land are farmed as Bourgogne Rouge. Bourgogne Passetoutgrains is for wines that are a blend of Gamay and (a minimum of a third) Pinot Noir made throughout the region. Significant amounts are made, but most is consumed in France. Côteaux Bourguignons was created in 2013 and allows the inclusion of Pinot Noir, Gamay and Cesar (in the Chablis area) in any proportion. This appellation is mostly used for Gamay from the Beaujolais region, which can now be reclassified into a theoretically more commercial appellation.

The Crus in the Côte de Nuits

The Red Grand Crus

The following list details the number of hectares of each Grand Cru, the number of different owners in the Grand Cru, average total production and a subjective list of the most famous producers, with the area they hold in brackets. At the end is a short list of Premier crus that regularly produce wines of Grand Cru quality, share similar geology and micro-climate to neighbouring Grand Crus and which could make a legitimate claim that they should be re-classified. All the red Grand Crus are in the Côte de Nuits with the exception of Corton.

Mazis-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 9.1 Ha; Average production: 3,500 cases; Number of Owners: 28; Important Producers: Joseph Faiveley (1.21Ha), Armand Rousseau (0.53Ha), Leroy (0.26Ha), Joseph Roy (0.12Ha).

Deep coloured and firmly structured with black fruit profile and excellent ageing potential, the wines are similar to Clos de Bèze and can be nearly as fine.

Ruchottes-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 3.3 Ha; Average production: 1,120 cases; Number of Owners: 7; Important Producers: Armand Rousseau (1.06Ha), Georges Mugneret-Gibourg (0.64Ha), Roumier (0.54Ha).

Austere in youth with tight tannins and notably acidity and leaning more toward red fruits. Good Ruchottes needs time to open out and gain weight.

Chambertin Clos de Bèze

Key info: Area under vine: 15.39 Ha; Average production: 5,100 cases; Number of Owners: 18; Important Producers: Armand Rousseau (1.42Ha), Drouhin-Laroze (1.39 Ha), Faiveley (1.29 Ha), Bruno Clair (0.98 Ha), Louis Jadot (0.42 Ha), Robert Groffier (0.47 Ha).

With Chambertin, the greatest of Gevrey’s Grand Crus, Clos de Bèze is perhaps a little less muscular but has finer aromatics. Bèze tends to produce fruit a fraction riper than Chambertin, giving deeper colours and more generosity when young. Unlike Chambertin, nearly all the growers here are good, so it is one of the most reliable Grand Crus to buy.

Chapelle-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 5.49 Ha; Average production: 1,820 cases; Number of Owners: 9; Important Producers: Ponsot (0.7Ha), Jean-Louis Trapet (0.6Ha), Drouhin-Laroze (0.51Ha), Louis Jadot (0.39Ha).

More elegant and lighter than the best Gevrey Grand Crus, it is often the fruitiest and takes to new oak less well than the others.

Griotte-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 2.69 Ha; Average production: 1,010 cases; Number of Owners: 9; Important Producers: Ponsot (0.89Ha), Joseph Drouhin (0.53Ha), Jean-Marie Fourrier (0.26Ha).

Well structured but with charm in its youth, it mingles redcurrant with darker fruits and a floral note. Hard to find, this is one of the best Grand Crus of Gevrey.

Charmes-Chambertin & Mazoyères-Chambertin

As Mazoyères is entitled to be sold as Charmes and the vast majority is, these two are best considered as one.

Key info: Area under vine: 30.83 Ha (Charmes 12.24 Ha, Mazoyères 18.59 Ha); Average production: 12,230 cases; Number of Owners: 67; Important Producers: Perrot-Minot (1Ha Charmes, 1 Ha Mazoyères), Armand Rousseau (1.37Ha), Dujac (0.7Ha), Ponsot (0.3 Ha), Roumier (0.27 Ha).

Full of fragrance and finesse, Charmes is the earliest maturing of the Gevrey Grand Crus and by virtue of its size and the number of producers, the one most likely to disappoint. Many producers swamp the wine with oak (Rousseau on the other hand uses little or no new oak for this vineyard), however Charmes from the best handful of producers is delightful inside a decade.

Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 12.9 Ha; Average production: 5,250 cases; Number of Owners: 25; Important Producers: Armand Rousseau (2.15Ha), Jean-Louis Trapet (1.9Ha), Rossignol-Trapet (1.6Ha), Jacques Prieur (0.84Ha), Leroy (0.5Ha), Dujac (0.29Ha), Ponsot (0.2Ha), Denis Mortet (0.15Ha).

The most structured and powerful of the Grand Crus, good Chambertin needs well over 10 years to begin to show its complexity. Dark, tannic and austere in youth, with black fruit flavours and notes of liquorice, it will never have the svelte finesse of Musigny, but more than makes up for it by its sheer presence. Sadly not all the growers here make the most of their terroir and there are plenty of examples of hard, overpriced wine.

Latricières-Chambertin

Key info: Area under vine: 7.35 Ha; Average production: 3,390 cases; Number of Owners: 10; Important Producers: Faiveley (1.21Ha), Rossignol-Trapet (0.76Ha), Jean-Louis Trapet (0.73Ha), Arnoux-Lachaux (0.5Ha).

Full robust and sturdy, Latricères can make very good wine but seldom does it justify its Grand Cru status.

Clos de la Roche

Key info: Area under vine: 16.9 Ha; Average production: 6,120 cases; Number of Owners: 40; Important Producers: Ponsot (3.4Ha), Dujac (1.95Ha), Armand Rousseau (1.48Ha), Hubert Lignier (1.01Ha), Leroy (0.5Ha).

In style Clos de la Roche is similar to Chambertin, although generally a touch richer and more forgiving, with power and austerity when young leading to great aromatic complexity after a decade in bottle.

Clos-St.-Denis

Key info: Area under vine: 6.63 Ha; Average production: 2,250 cases; Number of Owners: 20; Important Producers: Dujac (1.29Ha), Ponsot (0.7Ha), Bertagna (0.53Ha), Jadot (0.17Ha).

Markedly different to its neighbour Clos de la Roche, St. Denis is elegant and very aromatic with floral notes and red fruits. Deep and rich but with less structure than Clos de la Roche or Bonnes-Mares.

Clos des Lambrays

Key info: Area under vine: 8.84 Ha; Average production: 2,770 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: Domaine des Lambrays (monopole).

Despite a reputation as the finest terroir in Morey, when Grand Crus were being classified in the 1930’s the owner of Lambrays did not seek classification so as to avoid higher taxes. Thus this vineyard located between Clos de Tart and Clos-St.-Denis was passed over. In 1981 it was upgraded, although the wines over the previous 40 years were very hit and miss. Purchased by the Freund family in 1996, money was lavished on the estate and the quality soared to its historic levels with wines of balance power and finesse. This is the largest Grand Cru under single ownership and was bought in 2014 by LVMH for €100 million.

Clos de Tart

Key info: Area under vine: 7.53 Ha; Average production: 2,300 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: Mommesin (monopole).

This vineyard has had only 3 owners in 875 years and for nearly all its history it was renowned as one of the finest, although the wines of the 70s, 80s and early 90s were distinctly patchy. Since 1996, only the best parts of the vineyard have been bottled as a Grand Cru with the rest being sold as premier cru Forge du Tart. Seductive and perfumed, it is oaky in its youth (it is matured in 100% new wood), but develops a lovely earthy note with maturity.

Bonnes-Mares

Key info: Area under vine: 15.06 Ha; Average production: 5,120 cases; Number of Owners: 35; Important Producers: de Vogue (2.66Ha), Robert Groffier (1Ha), Dujac (0.58Ha), Bruno Clair (0.41Ha), Roumier (0.39Ha), Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier (0.36Ha), Jadot (0.27Ha), Leroy (0.26Ha), Joseph Drouhin (0.23Ha).

There are two distinct Bonnes-Mares, the upper sector in the north-east where the wines have higher acidity more marked tannins and greater finesse and the lower sector, towards Chambolle and lower down the slope, where the soils are deeper and iron rich and from where the wine is fruitier, fuller bodied and softer. The best producers have vines in both sectors and blend them, producing a wine of broad muscularity.

Musigny

Key info: Area under vine: 10.7 Ha; Average production: 2,904 cases Red, 240 cases White; Number of Owners: 17; Important Producers: de Vogue (6.46Ha of Pinot, 0.65Ha of Chardonnay), Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier (1.14Ha), Prieur (0.76Ha), Joseph Drouhin (0.68Ha), Leroy (0.27Ha), Jadot (0.17Ha), Roumier (0.1Ha), Faiveley (0.03Ha).

Along with La Tâche and Romanée-Conti, Musigny is burgundy’s finest Grand Cru and makes amongst the world’s greatest wines. A case study in elegance and subtlety, Musigny also has great underlying power and is a very textural wine. Usually described as ‘velvety’ or ‘silky’, words cannot really describe the beauty of it. In youth it can be austere, full of red fruits and with fine acidity and tannins. With age it develops notes of game, truffle, rose and violet that are exotic and intense. Great Musigny (and most of the producers of it are great) pulls off the trick of being powerful without ever seeming it.

Clos de Vougeot

Key info: Area under vine: 50.96 Ha; Average production: 17,520 cases; Number of Owners: 82; Important Producers: Méo-Camuzet (3Ha), Jadot (2.15Ha), Leroy (1.91 Ha), Grivot (1.86 Ha), Faiveley (1.29 Ha), Anne Gros (0.93 Ha), Ponsot (0.4 Ha), Denis Mortet (0.31 Ha).

It is very hard to generalise about Vougeot as the clos is large, with many owners of different skill and ambition and varying soil types and micro-climates. At its best it has some of the elegance of Volnay layered over the tannins of Gevrey, however much (most?), especially from the négoce, is a bit rustic and dull.

Echézeaux

Key info: Area under vine: 37.69 Ha; Average production: 12,661 cases; Number of Owners: 84; Important Producers: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (4.67Ha), Mongeard-Mugneret (2.5Ha), Lamarche (1.34Ha), Mugneret-Gibourg (1.24Ha), Gros Frère et Soeur (0.93Ha), Faiveley (0.83Ha), Jean Grivot (0.84Ha), Arnoux-Lachaux (0.8Ha), Anne Gros (0.76Ha), Dujac (0.69Ha), Jadot (0.52Ha), Méo-Camuzet (0.44Ha), AF Gros (0.28Ha).

A large Grand Cru of very variable quality that was over expanded for political reasons now encompassing 11 different climats. Much of Echézeaux is not worthy of Grand Cru status, indeed the premier cru Les Suchots frequently outperforms it, with perhaps only the mid-slope section regularly worthy of the name. Generalisation is impossible as wines from the deeper clay soils at the bottom of the slope can be quite rustic, whereas those at the top are often quite light and (in poor vintages) weedy. The best Echézeaux is usually rich and mouth filling with a mix of red and black fruits and with the finesse of Vosne.

Grands-Echézeaux

Key info: Area under vine: 9.13 Ha; Average production: 3,060 cases; Number of Owners: 21; Important Producers: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (3.53Ha), Mongeard-Mugneret (1.32Ha), Joseph Drouhin (0.48Ha), Gros Frère et Soeur (0.37Ha), Lamarche (0.3Ha).

Tight and ungenerous in youth, with a decade in bottle the aromatic complexity blossoms, with tertiary notes of game and leather, dark cherry and raspberry fruit and subtle florality.

Richebourg

Key info: Area under vine: 8.03 Ha; Average production: 2,700 cases; Number of Owners: 10; Important Producers: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (3.53Ha), Leroy (0.78Ha), Gros Frère et Soeur (0.69Ha), AF Gros (0.6Ha), Anne Gros (0.6Ha), Ligier-Belair (0.55Ha), Méo-Camuzet (0.34Ha), Jean Grivot (0.31Ha), Mongeard-Mugneret (0.31Ha).

One of the finest of the Grand Crus and the most opulent, combining elegance with great depth and sweetness of fruit. Sumptuous in youth, albeit often with marked acidity and rich fine tannins they are possessed of a lovely texture. With the ability to age for decades they have beautiful harmonious balance and often develop exotic spices and coffee notes.

La Romanée

Key info: Area under vine: 0.85 Ha; Average production: 340 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: Comte Ligier-Belair (monopole).

Located directly above Romanée-Conti and abutting Richebourg, this is the smallest Appellation Contrôlée in France and theoretically one of her finest terroirs, indeed there is some evidence it may at one time have been a part of Romanée-Conti. Owned by the Ligier-Belair family for nearly 200 years, for most of the 20th century the wine was of no great quality and half of the crop was marketed by Bouchard Père, an arrangement that continued until 2005. The last decade has seen great advances and the wine is slowly again taking its place at the top table of Grand Crus. Relatively firm and structured, but with plenty of flesh, it needs a decade to show layers of complexity.

Romanée-Conti

Key info: Area under vine: 1.81 Ha; Average production: 460 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (monopole).

For many this is the finest wine in the world, made from a tiny vineyard, in microscopic quantities and costing a king’s ransom (the 2015 is currently over £20,000 a bottle, whilst the 1945 can be bought for £430,000). Whilst the soils are very similar to La romanée,La Grand Rue and La Tâche, Romanée-Conti enjoys a perfect slope and aspect (almost due east) maximising sunlight exposure and allowing a degree more ripeness and richness in the finished wine, whilst maintaining the acidity and vigour. The wine itself is less obvious than la Tâche or Richebourg when young, being paler and more elegant than both, but the sheer complexity of flavour and incredible persistence mark it out as something even beyond these two greats.

La Grand Rue

Key info: Area under vine: 1.63 Ha; Average production: 600 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: François Lamarche (monopole).

Like Clos du Tart, this was not made a Grand Cru in the 1930s as the Lamarche family wanted to avoid higher taxes and did not put it forward, despite it being sandwiched between La Tâche, Romanée-Conti and La Romanée! After geological studies it was promoted to Grand Cru in 1992, despite this being a period when the wines made here were poor. Recent years have seen a cut in yields and more careful vinification and at their best, the wines resemble La Tâche with floral red fruits, superb concentration and fine structure, however there have been too many poor vintages in the last 30 years considering how fine the terroir is.

La Tâche

Key info: Area under vine: 6.06 Ha; Average production: 1,600 cases; Number of Owners: 1; Important Producers: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (monopole).

In the same ownership as Romanée-Conti since the 1860s and the only vineyard in burgundy to regularly rival it for quality, the majority of La Tâche is now planted with sélection massale plant material from its stable-mate. Comparing it to Romanée-Conti is invidious as both are wines of other-worldly complexity, but side by side, La Tâche is always darker coloured and has greater substance than Romanée-Conti – it is more similar to Richebourg but with greater finesse and seems to continue to develop flavours in the mouth minutes after tasting. Refined and velvety textured, fine vintages need 15 years to reach maturity and will keep developing over decades.

Corton

Key info: Area under vine: 160 Ha; Average production: 78,400 cases of Red, 28,300 of Corton-Charlemagne White; Number of Owners: 200 (a further 75 for White); Important Producers: Comte Senard (3.72Ha), Bouchard Père (3.25Ha), Faiveley (3.02Ha), Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (2.27Ha), Louis Jadot (2.1Ha), Chandon de Brailles (1.9Ha), Tollot-Beaut (1.51Ha), de Montille (0.84Ha), Jacques Prieur (0.73Ha), Leroy (0.5Ha), Méo-Camuzet (0.45Ha), Joseph Drouhin (0.26Ha).

The last of the red Grand Crus and the only one to be situated in the Côte de Beaune, Corton covers a massive and varied area wrapping around the hill of Corton, with its distinctive forest on the top and as such is very difficult to pin down. Spread across three communes and 25 climats, this is the only grand cru that allows the individual climat to be listed after the name (for red wines only).

The appellation rules are fairly convoluted but quite clear, Corton can be used for red or white wine (95% is red and the white must be labelled ‘Corton Blanc’), whilst Corton-Charlemagne is reserved for whites made on the designated best sites for Chardonnay (red wine made in these climats can only call itself Corton).

The best reds tend to come from the mid slope on the east facing side – the climats of Les Renards, Le Clos du Roi and Le Corton are best, followed by Les Bressandes, Pougets and Perrières. Sad to say, but the majority of Corton is not worthy of Grand Cru status, being fairly hefty, a bit coarse and lacking in aromatic complexity. From the producers listed above – especially Faiveley, Senard, DRC, Jadot and Chandon de Brailles – it can be magnificent, rich, mouth-filling, full bodied and quite gamey, developing beautifully in bottle.

Red Premier Crus with a legitimate claim to Grand Cru status

Gevrey-Chambertin Clos St Jacques

Key info: Area under vine: 6.7 Ha; Average production: 2,950 cases; Number of Owners: 5; Important Producers: Armand Rousseau (2.22Ha), Bruno Clair (1.0Ha), Louis Jadot (1.0Ha).

Easily confused for Chambertin, the wines from here, especially Rousseau’s usually surpass those made in all but Chambertin and Clos de Bèze. Highly priced for a 1er cru, but a relative bargain.

Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses

Key info: Area under vine: 5.4 Ha; Average production: 2,300 cases; Number of Owners: 17; Important Producers: Robert Groffier (1.0Ha), de Vogue (0.56Ha), Jacques-Frèderic Mugnier (0.53Ha), Roumier (0.4Ha), Louis Jadot (0.12Ha).

The market reflects how good this vineyard is and on occasion it priced higher than Bonnes-Mares from the same source. Similar in style to Musigny, it really should be a Grand Cru.

Vosne-Romanée Cros Parantoux

Key info: Area under vine: 1.01 Ha; Average production: Not Known; Number of Owners: 2; Important Producers: Méo-Camuzet (0.7Ha), Emmanuel Rouget (0.3Ha).

Adjoining the top corner of Richebourg, the late Henri Jayer bought and replanted this vineyard, which had been abandoned after phyloxerra and turned it into the superstar 1er cru of Vosne. Grand cru in quality and price.

Pommard Les Rugiens du Bas

Key info: Area under vine: 5.83 Ha; Average production: Not Known; Number of Owners: 14; Important Producers: de Courcel (1.07Ha), Michel Gaunoux (0.69Ha), de Montille (1.0Ha), Louis Jadot (0.36Ha).

The Rugiens vineyard has applied for Grand Cru status and may well get it (along with Les Epenots in Pommard), but the section that truly deserves it is the Bas part of Rugiens, which makes wines of muscle and density, but also great finesse.

Others with a claim to this list: Vosne-Romanée Les Malconsorts, Nuits-St.-Georges Les Saint-Georges, Volnay Les Caillerets and Pommard Les Epenots.

Market

The region now exports over 7 million cases and €1 billion worth of wine with the USA (22% of all exports) and UK (17%) the two largest markets (we import 1.2 million cases worth €146 million). Other significant markets include Japan, Canada, Belgium, Sweden and Germany. White wine makes up 60% of the total (with nearly 40% of that coming from the Maconnais and a quarter as Bourgogne Blanc), red wine 29% and Crémant 11%. Around a third of the red wine volume comes from the prized region of the Côte d’Or villages, with just under half being Bourgogne. Chablis exports have declined in the past couple of years owing to small harvests and rising prices. Volumes are split roughly equally between domaine bottlers on one side and 250 merchants and co-operatives on the other side. Prices have risen well ahead of inflation for two decades now and worldwide demand continues to grow.

Recent and Great Vintages

1978: A legendary year and still great. Even the best whites are also still going.

1985: Precocious, these were delicious from the word go, though only the best are still going.

1988: Hard work when young with a firm tannic backbone, these are very worthwhile now.

1989: Another forward and sumptuous vintage that have survived better than expected. Still charming.

1990: Nearly the match of 1978 (and with better winemaking the overall standard perhaps higher). Really great wines.

1995: Some were a little charmless in youth, but many developed very well and are still drinking well now.

1996: An unusual vintage led to a ripe and healthy crop but with some of the highest acidity levels seen. They have developed very slowly and a few have faded leaving sourness behind, however there are some real gems and some fine whites still going strong.

1997: Pleasant and easy going, but mostly well past it now.

1998: Dark and tannic and mostly lacking charm.

1999: A brilliant year across the board and good examples are excellent now.

2000: An average year that drank well young and have faded badly.

2001: Wet and hot made this tricky. Those who got it right made lovely wines for long ageing, others were just thin and hard.

2002: Very good vintage, some fading now.

2003: Too hot for most, the wines were baked and died young. A few wines from venerable vines were exceptional, but they are the exception themselves.

2004: Large crop and approachable, but few worth drinking now.

2005: Really fine year and the best just reaching their apogee.

2006: Not great weather led to not great wines. Serviceable, but not much more.

2007: Damp with rot problems. Mostly one to forget.

2008: Another year of rain and disease pressure. High acidity, but some have turned out better than expected.

2009: After 3 poor years, 2009 was greeted as a saviour. Very good if not great, they drank well young and are still mostly lovely now.

2010: A good but structured vintage with good ageing potential.

2011: Some good wines, but many were thin and lacked purity.

2012: Very mixed weather with similarly mixed quality. Generally soft and easy-going, few superstars.

2013: Small crop and a difficult year, but the wines ended up better than average and are worth keeping.

2014: Light and fruity, this was a much better year for whites, however the reds are not without their charms for drinking now.

2015: Hot year with some indisputably fine, even great wines. Some are a little flabby and should be drunk now, but most are well worth keeping.

2016: Low yields and a difficult year. Some very good wines, some very poor.

2017: Soft, fruity and approachable, there are some charming wines here. This will probably end up in the ranks of very good rather than great, but time in bottle may change that.

2018: A large and homogenous vintage with even the lesser wines performing well. They may lack structure for really long ageing, but this is certainly a fine year.